-

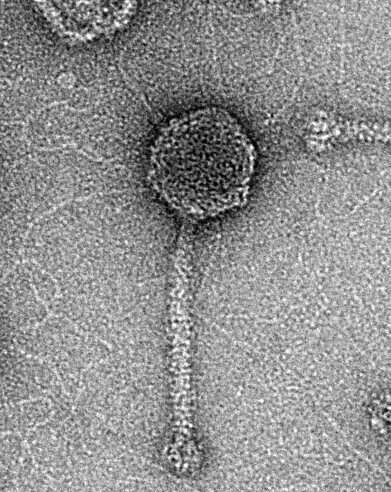

Microscope image of phage virus. (Credit: Biomedical Imaging Unit, UHS.)

Microscope image of phage virus. (Credit: Biomedical Imaging Unit, UHS.) -

-

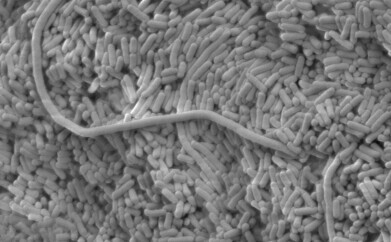

Microscope image of bacteria. (Credit: Biomedical Imaging Unit, UHS)

Microscope image of bacteria. (Credit: Biomedical Imaging Unit, UHS)

Research News

Combined bacterial defences ward off viruses

Mar 18 2024

Scientists at the University of Southampton have discovered how bacteria can pair up their defence systems, creating a formidable force to fight off attack from phage viruses. Because phage viruses, or bacteriophages, can kill harmful bacteria without affecting the good bacteria in our bodies, an understanding of how bacteria respond to attacks of this kind could be crucial in exploring how phage viruses might be harnessed to fight infections as an alternative to antibiotics.

Lead author of the study, Dr Franklin Nobrega of the University of Southampton’s School of Biological Sciences said: “Just like how our immune system protects us from harmful germs, bacteria have their own set of defence systems which create a dynamic shield against viral threats. Imagine if your white blood cells, antibodies and killer T-cells all joined forces to fight off a virus together. This is exactly what is happening inside bacterial cells.

“We used to think of bacterial defence as a solo act, but it turns out it’s more like a buddy system. A ‘dynamic duo’ of defence systems merge their powers to mount a stronger response than they otherwise would have achieved, potentially saving the cell from destruction.”

Using existing datasets of paired defence systems in the genomes of some 42,000 bacteria, including E. coli, the researchers looked for those that appeared more frequently then would normally be expected. A selection of these were tested in the lab for enhanced virus immunity and, crucially, ‘synergy - a defence effect in the bacteria which is more powerful than the sum of its parts.

From identified enhanced systems and with further testing, they were able to see for the first time how the partnerships between individual bacterial defences are based on one system using a function from another to improve its activity. Combined, they have a more robust effect than working apart.

Phages are already in use as a last-resort treatment for antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections, a practice known as phage therapy. But by delving into how bacteria defend against these phages, we can supercharge our strategies to make them even more effective at wiping out bacterial cells, offering a glimmer of hope in the battle to keep infections at bay, Dr Nobrega added.

The scientists added that their research will complement efforts already underway to develop phage therapy through public participation initiatives such as The Phage Collection Project and the open science KlebPhaCol project.

The funding for this study was from the Wessex Medical Trust and the National Institutes of Health USA. Findings were published in Cell Host & Microbe.

More information online

Digital Edition

ILM 49.5 July

July 2024

Chromatography Articles - Understanding PFAS: Analysis and Implications Mass Spectrometry & Spectroscopy Articles - MS detection of Alzheimer’s blood-based biomarkers LIMS - Essent...

View all digital editions

Events

Jul 28 2024 San Diego, CA USA

Jul 30 2024 Jakarta, Indonesia

Jul 31 2024 Chengdu, China

ACS National Meeting - Fall 2024

Aug 18 2024 Denver, CO, USA

Aug 25 2024 Copenhagen, Denmark

-with-research-lead-Dr-Sandro-Ataide-and-first-author-Rezwan-Siddiquee-(right)---C.-Photo-Fiona-Wolf-USYD.jpg)

24_06.jpg)