-

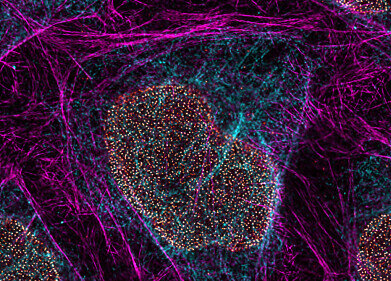

The technique could be developed as a chromosome treatment for those born with Down's syndrome

The technique could be developed as a chromosome treatment for those born with Down's syndrome

Microscopy & Microtechniques

Scientists repress Down's syndrome extra chromosome

Jul 19 2013

Scientists in the US may soon reach the point where they are able to treat disorders such as Down's syndrome by turning off the extra chromosome that causes them. Experiments in the laboratory at University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMASS) have so far resulted in the successful blocking of the extra chromosome in human cells. This has increased the hopes for a successful treatment of the disorder.

Down's syndrome affects around 750 babies in Britain each year, whilst globally around one in every 1,000 babies is born with the disorder. The disorder occurs when a baby is born with an extra chromosome, meaning it has three copies of chromosome 21 instead of the usual 23 chromosome pairs.

This extra chromosome 21 causes some problems with overall health, including disrupted immune system, heart defects and a higher chance for developing leukaemia during childhood. It also causes developmental issues and learning difficulties.

The most recent study has found that the extra chromosome can be repressed, or 'switched off', within cells in a laboratory environment. This has only ever been done before for a single gene, meaning that the most recent find is a huge breakthrough.

As well as signalling that the chromosome could possibly be repressed in a live person in the future, the finding also provides a new insight into the ways in which the genome can be further affected by the disorder. There is a chance that genetic pathways could eventually be highlighted that could allow other disorders to also be repressed and help to prevent genetic diseases.

Whilst a chromosome therapy is still some way, the research could help in the development of therapies that could help treat some of the common problems and symptoms of Down's syndrome.

Jeanne Lawrence, leader of the UMASS team, said: "This will accelerate our understanding of the cellular defects in Down's syndrome and whether they can be treated with certain drugs. The long-range possibility – and it's an uncertain possibility – is a chromosome therapy for Down's syndrome. But that is ten years or more away. I don't want to get people's hopes up."

Digital Edition

Lab Asia 31.2 April 2024

April 2024

In This Edition Chromatography Articles - Approaches to troubleshooting an SPE method for the analysis of oligonucleotides (pt i) - High-precision liquid flow processes demand full fluidic c...

View all digital editions

Events

May 21 2024 Lagos, Nigeria

May 22 2024 Basel, Switzerland

Scientific Laboratory Show & Conference 2024

May 22 2024 Nottingham, UK

May 23 2024 Beijing, China

May 28 2024 Tel Aviv, Israel

.jpg)